How to Experience a Hammam – An Introduction to the Hammam Culture and Bathing Ritual

A hammam is a unique, millennia-old bathing tradition. Today, you can still enjoy this experience in many historically significant Turkish bathhouses. But how does one behave in a hammam? Are the oldest hammams in Istanbul really over 500 years old? This second article in Saunologia’s hammam series guides the reader into the world of Istanbul’s bath culture, which has enjoyed a renaissance in this millennium.

Bathing Under the Wings of History

The oldest known hammams date back to the 8th century in the Middle East. One of them, Qusayr Amra, a desert castle in Jordan and a UNESCO World Heritage Site, still stands today. In Turkey, the golden age of hammams began in the 14th century in Istanbul. Over the following centuries, many were built, and surprisingly, several hammams from the that period are still in use today!

For example, opposite Istanbul’s top attraction, the Hagia Sophia, stands the Hürrem Sultan Hammam, opened in 1556. According to a 1638 census, the city then had 14,536 private and public baths! Public baths were local and often specialized—different tradespeople bathed in different establishments.

In 2025, the oldest functioning baths in Istanbul include the hammam at Beyazit Square from 1481 and the Tarihi Örücüler Hammam by the Örücüler Gate (Weavers’ Gate) of the Grand Bazaar, dating to 1465. Like many others, the Örücüler Hammam has been modernized over time—even featuring a unique sauna today! In fact, saunas have become a trendy feature in many small, modernized hammams and are surprisingly popular in Turkey.

The oldest operating hammams are over 500 years old.”

Walking into these buildings, the historical atmosphere is palpable, as the entire old city center echoes with memories of bygone times. Around the Grand Bazaar (Kapalıçarşı Mercan Gate), several small historical hammams can be found in addition to the aforementioned Tarihi Hammam.

Home Baths Dried Up the Public Bath Culture

Not all hammams that prominently advertise their founding year have operated continuously as luxurious bath houses for centuries. For example, the Zeyrek Cinili and Kilic Ali Pasa hammams, both designed by the famous architect Mimar Sinan, had deteriorated in use or disuse until they were lavishly restored in this millennium.

This 20th-century story sounds familiar—hammams experienced a fate similar to public saunas in Finland. As private bathrooms improved, public baths became unnecessary and mostly served only a small niche. Funds were insufficient to maintain large buildings. For a while, the sauna even became a more popular luxury in Turkey than the hammam!

But in this millennium, the situation has changed, says local expert Elizabet Kurumlu. Now, hammams are once again popular among 20–40-year-old city dwellers, in addition to being frequented by many tourists. However, hammams are not visited daily or even weekly—an average Turkish person might go once a month. This, of course, affects the business model of these privately owned spas.

How to Bathe in a Hammam: Arrival and Dressing

A hammam is primarily a bathing service. Many hammams have separate sections for men and women, but for example, Kilic Ali Pasa Hammam (in Turkish, Kılıç Ali Paşa Hamam) operates a single bath area with alternating hours for men and women (8:00–16:00 for women, 16:30–23:00 for men). Many hammams are open at least 12 hours a day. Anyone interested should check opening hours online—most hammams have at least a Turkish-language website or social media profile. Basic information is usually also available on Google Maps.

Upon entering during open hours, one typically has to descend stairs—the ground floors of old buildings are usually well above street level. Hammams are thus not particularly accessible. In some places, you remove your shoes shortly after entering; in others, you first encounter the reception desk.

At the reception, you pay for your service and may receive bath equipment and instructions for using the changing rooms. Many places offer additional services beyond the basic price, such as barbers. Historically, service options were broader, especially for women, but many beauty services have relocated outside hammam walls.

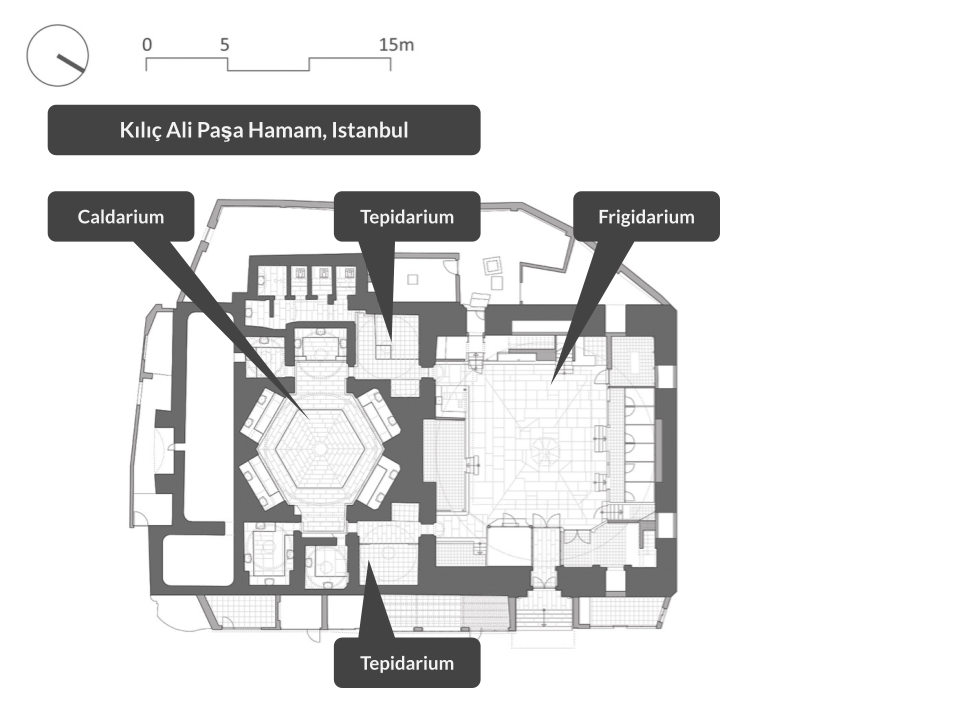

After paying, staff will guide you to the changing area, where you swap your clothes for bath attire. For a description of the typical hammam architecture (frigidarium, tepidarium, caldarium), please see the previous article and the illustration below.

Hammam Attire: Nalin and Peshtemal

Essential hammam items include sandals—either traditional wooden-soled ones (nalin) or modern ones—and the peshtemal, a light cotton wrap, known in Finnish as a “hammam towel.”

With traditional footwear, one had to walk slowly and carefully, Elizabeth explains. This influenced the bathing experience—fast-paced city walk was replaced with mindful steps in the hammam.

The peshtemal is a thin cotton wrap used throughout the bath if desired. Alternatively, you can bathe nude (only in the hot room during the wash!) or wear disposable undergarments, which are available in some hammams. The classic style of the peshtemal features stripes and fringes, which supposedly help the towel dry faster. You can see examples of these towels and traditional laundry setups in the image from Cemberlitas Hammam.

Into and Through the Bath

After getting ready, you return to the entrance hall (frigadarium). From there, staff guide you into the warmer rooms. Now is your last chance to visit the toilet.

The actual washing ritual starts in the caldarium, a hot stone room often featuring a central platform (göbek taşı or “belly button stone”) under a dome.

The steps that follow vary slightly by place. First, the customer is thoroughly rinsed with warm water and then left to warm up. This warming phase is almost meditative—you do nothing but wait until staff determine that your skin is ready for exfoliation. The goal is similar to what many sauna-goers experience—the surface layer of skin begins to loosen naturally.

The washing is called a soap bubble wash and can involve mitts of different coarseness. The process includes a thorough exfoliation (kese), focused on the upper body and back.

After the bubble wash, there’s a final rinse and possibly a light massage. Massage can be done either on the central stone or seated elsewhere. All clients are treated in the caldarium, and one personal attendant completes the ritual from start to finish. Throughout the process, the client does nothing but move from place to place.

Ergin Iren, the manager of Kilic Ali Pasa Hammam, explains that the traditional heart of the hammam ritual is the wash itself. The basic ritual is not massage therapy, but cleansing. You can purchase a massage in many hammams, performed by a skilled masseur, but it is not part of the traditional hammam experience.

Cooling Down

The final part of the ritual takes place in the warm room (tepidarium), where you dry off and are wrapped in towels. After that, you return to the entrance hall to cool down and enjoy refreshments—typically the ubiquitous Turkish black tea.

Even though the warming stage gets you quite hot, there are no sauna-like elements in the facility or ritual. Nor would I consider the bath as heat therapy per se. The hammam is about pampering and cleansing as a service, possibly also a shared experience and social time with friends.

During my stay in Istanbul, we visited the hammams in the early evening on a weekend and didn’t see groups larger than a few people. But it’s customary for locals to visit hammams in larger groups to celebrate traditional milestones.

Thanks to Elizabet Kurumlu and Ergin Iren for interviews and great company!

Yksi kommentti